The dawn of the 20th century saw a significant expansion of scientific teaching and research at the university. The creation and endowment of many new science departments at the end of the nineteenth century facilitated groundbreaking research and produced students ready to take on the unique challenges of the new century.

In this period:

- Physical science at the turn of the century

- Scientists at War

- A changing student body

- Building towards the Biology Department

- Carrie Derick, Canada’s first female professor

- Hidden gems – McGill’s early biological research and teaching aids

- Industry takes root – The Pulp and Paper Research Institute

- A new science of the mind: From philosophy to psychology

- Image Gallery

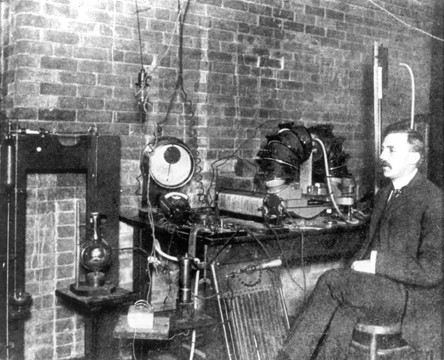

Physical science at the turn of the century

1897-1910

During the early 1900s, physics and chemistry flourished at McGill, building the foundations of today’s departments.

The development of physical sciences at McGill was spurred on by the construction of dedicated laboratories in the MacDonald Physics Building and the MacDonald Chemistry and Mining Buildings, as well as the endowment of a Chair in Physics. The physical sciences, physics and chemistry in particular, were a place of experimentation, exchange, and innovation during the first ten years of the 1900s. Young, ingenious scientists were attracted to the university, and in turn, helped produce a new generation of scientists who would go on to make significant, cutting-edge discoveries.

One such scientist was renowned physicist Ernest Rutherford. Rutherford arrived at McGill as a promising young scientist and departed on the cusp of being known as one of the most prominent physicists of his time. Rutherford was appointed as the MacDonald Chair in Physics at McGill in 1898, after undertaking a postgraduate fellowship under J. J. Thompson at Cambridge at the Cavendish Laboratory. Rutherford was soon joined by Frederick Soddy, a physicist from England. Soddy had originally sailed to Canada after applying for a job at the University of Toronto only to find out upon arrival that the position had already been filled. Luckily, there was an opening at McGill, and Soddy joined the faculty as a demonstrator in chemistry in 1901. Rutherford and Soddy worked closely together to explore a fundamental question of both physics and chemistry–radioactivity. Essentially, their work endeavored to understand the nature of matter. During Rutherford’s relatively short nine-year tenure at McGill, he created a huge body of work, publishing 69 papers. The magnitude of his work was recognized shortly after he left the university in 1907 by a Nobel Prize in Chemistry. Soddy served an even shorter tenure at McGill, departing in 1903. His research on radioactive decay and theorization of isotopes was recognized by the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1921. The research of both these scholars animated the physical sciences at McGill, contributing to a robust research program and drawing in future scientists.

During this period, many notable physicists were educated at McGill. One such scientist was Harriet Brooks, who trained under Rutherford. Brooks graduated with a First Class Honours B.A. in Mathematics and Natural Philosophy, and was awarded the Anne Molson Gold Medal for her outstanding academic performance. She continued as Rutherford’s first graduate student while also serving as a non-resident tutor at Royal Victoria College. In 1901, she became the first person to receive a Master’s degree in a scientific discipline at McGill. Following her graduation, she continued to work at McGill, conducting a series of experiments on the nature of radioactive emissions from thorium, a foundational issue in nuclear science. She would go on to work at Bryn Mawr College, Barnard College, and with Marie Curie in France. Her research was crucial to the discovery that the elements undergo some transmutation in radioactive decay.

Other notable graduates of the physical sciences include Robert William Boyle, an early pioneer in the development of sonar. Like Brooks, Boyle trained under Rutherford, receiving the first Ph.D. in physics in 1909. During the First World War, Boyle worked with French researchers to produce a working prototype of ASDIC, the first sonar. In the same year that Boyle was awarded a Ph.D., Annie Macleod became the first woman to be awarded a Ph.D. at McGill, as well as the first person to earn a Ph.D. in chemistry.

Scientists at War

1914-1918

The experience of war transformed the role of scientists at McGill and changed the importance and goal of research activity.

McGill University was not uniquely affected by World War I, however, its professors and students both made important contributions to the war effort. The war also brought forth the importance of scientific research on the world stage, which affected science at McGill for decades afterwards.

WWI was the first time in human history where both sides fully wielded technology, but also deliberately encouraged its further development by organized research. McGill was not immune to this trend, and as such, in the war years research priorities shifted. The pace of research greatly quickened at universities globally; research goals became highly defined, and applications of new discoveries eagerly sought, a change from earlier research endeavors.

Scientists also became recognized as highly important members of society, and as such, remained at the university to conduct research instead of fighting in the trenches. Professors were asked to stay back in their lecture rooms and labs, educating young men for technological and scientific warfare, and conducting research for the war effort.

Specifically, at McGill, professors and students in the Departments of Chemistry and Physics both made significant contributions to the war. The Department of Chemistry established a lab to study explosives and to develop protection against phosgene, the deadliest poison gas of the war. Two graduate students, H.W. Matheson and H.S. Reid also designed a basic process for manufacturing acetone (the key component for making cordite, an explosive propellant for military weapons) and applied this process to achieve mass production very quickly. As well, McGill chemistry students, led by metallurgy professor Alfred Stansfield, produced 400 pounds of magnesium a day. Magnesium was desperately needed to produce electrical cable and photographs. Professor Godfrey Burr and lecturer S.W. Werner also solved the seemingly impossible problem of manufacturing cadmium needed for field telephone cables. Their process remained secret during the war and was later carefully protected by patent.

Many McGill physics professors contributed directly to war time research as well and some were even recruited to research in the highest level of government in Britain. These scientists included Arthur Stewart Eve, Louis King, Etienne Bieler, and Robert William Boyle who all worked on various aspects of submarine detection. They notably contributed to the development of sonar technologies. Other technologies contributed to by McGill physicists included navigational aids in blacked-out harbours and sound-ranging location of enemy guns.

At McGill, the wartime experience of research gave these activities a new status in the university. From then on, engagement in research became recognized as a now necessary, and regular, part of professorial duties. Furthermore, the necessities of war shifted the value of research towards utilitarianism and the potential for applications became highly valued.

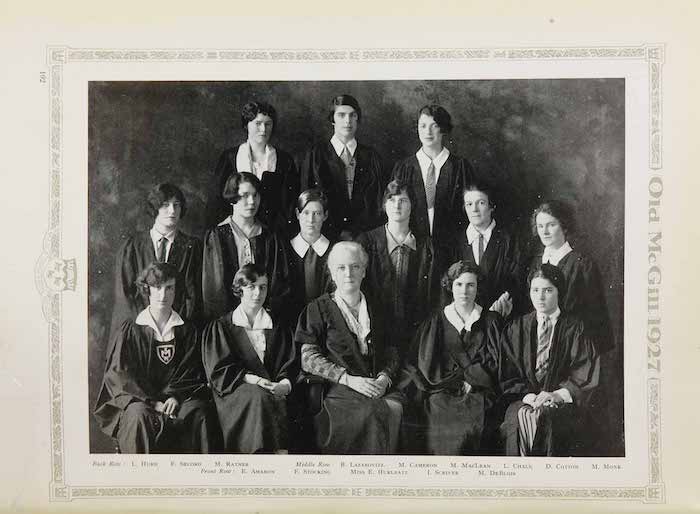

A changing student body

1900-1935

The beginning of a new century saw a change in the diversity of the student body across gender, racial, and ethnoreligious domains.

Prior to the turn of the century, the student body was almost exclusively white Anglo-Saxon, Christian, and male. However, this began to shift significantly around the start of the 20th century. The admission of women to McGill in 1884 signaled a massive shift in the university. By 1889, women comprised one third of the student body. In 1900, the Royal Victoria College building opened, with multiple women’s groups such as the Delta Sigma Society, the YMCA group, and the RVC Athletic Club established by 1905. Within science, as with all subjects, women were taught separately from men, however they received the same curriculum and had the same course requirements. During this period, Royal Victoria College fostered the education of many notable women scientists including Harriet Brooks in physics, Alice Vibert Douglas and Laura Rowles in physics, and Carrie Derick in biology. Between 1900 to 1930, the size of Royal Victoria College grew significantly, however upon graduation many women scientists were met with limited career options.

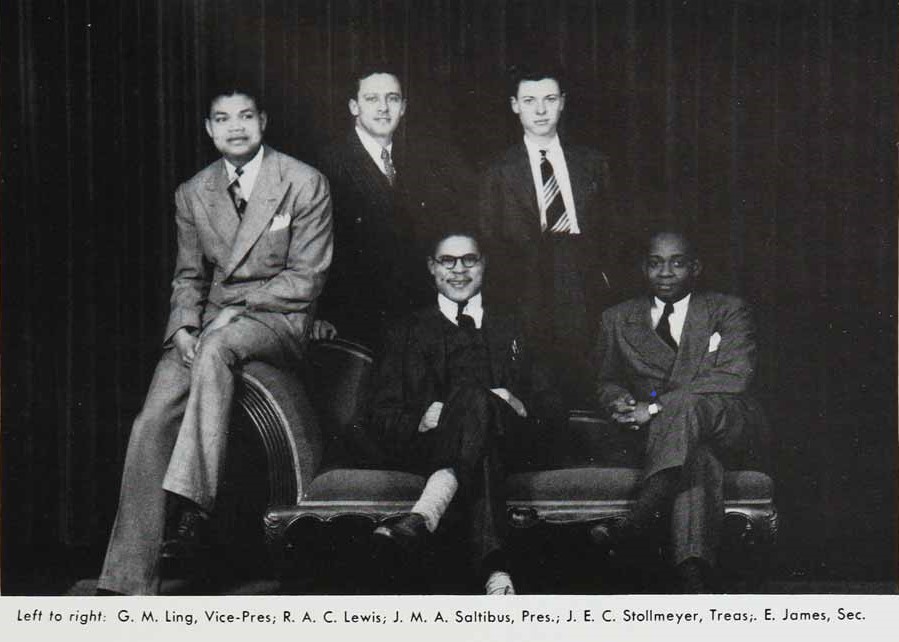

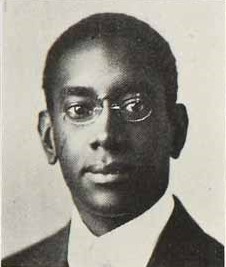

The racial diversity of McGill also began to change in the 1900s; however, it is more difficult to trace similar information about students of colour at McGill. For instance, student records at this time did not identify race, and so student yearbooks, which had photos and often places of origin, were used as a substitute resource. Though this information is still limited and likely does not capture the full breadth and diversity of students of colour at McGill, these records support the notion that students of colour, and specifically Black students, have been part of the McGill community for over a century.

Although it is important to recognize the presence of Black students at McGill to acknowledge their contributions to the community, this must be balanced by the knowledge that they have been structurally excluded from higher education. Despite the racial disparity from this systemic exclusion, a number of notable Black students graduated from McGill during this time. This is most evident in the Faculty of Medicine, which graduated prominent Black scholars, including George Edwin Thwaites (Class of 1907), A.C. Harry (Class of 1908), A.M. Fyfe (Class of 1909), Henry T. Strudwick (Class of 1910), and Thad Dyden (Class of 1911). It is likely that the first Black science student at McGill was David Cornelius Canegata Sr. who graduated with a BA in 1909 and from the McGill Faculty of Medicine in 1911. Canegata was originally from St. Croix, which is now part of the American Virgin Islands and was educated in boarding schools in Antigua. He was the first Crucian to become a physician and was a member of all three levels of government and an active humanitarian.

While the nature of the student body continued to grow and change throughout the first third of the 1900s, women, students of colour, and Jewish students continued to face both implicit and explicit exclusion and limitations within the university. An example of this can be seen very clearly by the administration’s treatment of Jewish students during this time. Throughout the early 1900s, the number of Jewish students increased, with Jewish students constituting 6.8% of the student body in 1913 and 25% of the student body in 1924. During this time, Jewish students built an active community within McGill, seen in the creation of the Maccabean Circle in 1905 and the Menorah Society in 1920. During this period, McGill administrations were concerned that the increase of Jewish students would come at the expense of “Anglo-Saxon” students, framing Jewish students as being too academically inclined and playing into larger anti-Semitic stereotypes. Beginning in 1929, McGill implemented policies to restrict Jewish students by increasing the admission grade average requirement to 70% for Jewish students and to 75% in the 1930s, while the entrance requirement for non-Jewish students remained at 60%. Within the Faculty of Medicine, there were more explicit quotas–with the percentage of Jewish students limited to 10% of the Faculty’s student population. By 1935, the proportion of Jewish students dropped to 12%.

Building towards the Biology Department

1880-1934

Predecessors to the modern Department of Biology, the former Departments of Botany, Zoology, and Genetics, experienced tremendous growth in the early twentieth century, leading to an expansion across both faculty members and physical infrastructure.

The Beginnings of Biological Sciences

Natural sciences and the nascent forms of today’s Department of Biology were among some of the earliest scientific departments at McGill. In the nineteenth century botany was an essential part of medical studies since the discipline relied heavily on herbal medicines. With Principal Dawson’s strong stewardship and fostering of the natural sciences at McGill, biological studies expanded to include increasingly specialised teaching positions and independent departments into the twentieth century.

Until the 1880s Dawson taught 10-14 hours a week. In need of reducing his workload, he hired David Penhallow to take over botany lectures. By 1885, botany became its own specialised study with a Chair of Botany and Vegetal Physiology held by Penhallow. In 1897, Lord Strathcona endowed a Chair in Zoology, which lured Ernest MacBride to McGill. MacBride brought expertise in microscopy and development from his studies in Europe – both now fundamental subjects in biology research.

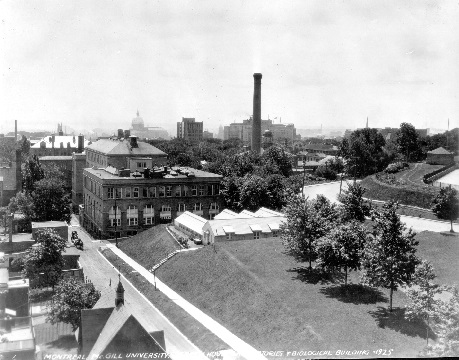

By the 1920s, biological sciences at McGill had expanded so much as to require a new building. In 1922, the university commissioned a new Biology Building to house both the traditional (botany and zoology) and the new (physiology, biochemistry, and pharmacology) biological sciences under one roof. Nearby, an animal house and a conservatory were constructed. Eventually requiring even more space and modernized laboratories, biology moved again in 1965 and the old biology building became the now familiar James Administration Building. An ornamental stone frog remains above the entryway of the building, a reminder of the building’s original purpose and the decades of important biological research and teaching which took place within.

Carrie Derick (1862-1941) and the Department of Genetics

By the 1930s, the strength of biological research at McGill necessitated the creation of a new independent Department of Genetics. The Molson family funded a Chair in Genetics in 1934, formalising decades of pioneering research. This new department accounted for the rapidly growing knowledge and expertise in this emerging field, in part due Prof. Carrie Derick’s innovative work in the Botany Department in the early decades of the twentieth century.

Carrie Derick, in 1912, after two decades of teaching, researching, and administrating at McGill University, became the first female professor in Canada. Despite setbacks and lack of recognition, Derick truly pioneered biological sciences at McGill and in Canada. She introduced a course “Evolution and Genetics” at McGill, the first of its kind in Canada. During her undergraduate studies, evolution was still an incredibly controversial subject, and genetics only just an emerging field. She helped science at McGill become increasingly cutting-edge and relevant, sparking the large-scale study of genetics at McGill, and the creation of the first Department of Genetics in Canada.

The independent departments of Genetics, Zoology, and Botany joined together to form the modern Department of Biology in 1970.

Read more below about McGill’s early biological research and teaching aids.

Carrie Derick: Canada’s first female professor

1862-1941

During her impressive career as a scientist and educator, Derick persevered through a number of obstacles, and forged a path for women’s rights to education and work.

Carrie Derick is lauded as the first female professor at any Canadian university; however, this simple phrase does not give credit to her impressive career as a scientist and educator, regardless of her gender, nor does it adequately address the barriers she faced throughout her career despite the title of professor.

Education and Early Career

Born January 14, 1862 in Clarenceville, Quebec, Carrie Mathilda Derick first trained and worked as a teacher. She began teaching at the age of fifteen and later graduated from the McGill Normal School (now the Faculty of Education) in 1881 as a Prince of Wales Gold Medal winner.

McGill Years

Derick then enrolled in McGill’s Faculty of Arts in 1889 to study natural science. In 1890, she graduated at the top of her class, winning prizes in zoology, classics, and the Logan Gold Medal in Natural Science. In 1891, while maintaining two jobs, Derick began to work on her MA with botany professor David Penhallow. During her studies, she worked as a botany demonstrator, making her the first female academic staff member at McGill. After the completion of her MA in 1896, Penhallow recommended Derick as a full-time lecturer at McGill. However, the Board of Governors rejected this idea, instead offering her the lowest rank position of “Demonstrator.” This position paid $750 annually. For seven years she lectured, assisted Penhallow with his classes, and researched and published without any pay increase or offer of promotion. Finally, in 1905, Derick wrote directly to Principal Peterson and was promoted to assistant professor with a salary of $1250. By comparison, in the same year, male faculty received an annual salary of $3000.

During this time, she also began work for her Ph.D. in 1901 at the University of Bonn. Despite completing all the coursework and research by 1906, Derick was not awarded the degree because at the time, the University of Bonn did not grant doctorates to women.

Despite the institutional setbacks, Derick continued to work, teach, and administer in the Department of Botany. In 1909, Derick unofficially assumed the role of Chair of the department when Penhallow became ill and continued to run the department for three years following his death. When the university began a search for a new department chair, she had strong support from her colleagues, but ultimately was not offered the position despite her experience. Instead, in 1912, the university appointed her as Professor of Morphological Botany, making her the first woman at McGill and in Canada to achieve university professorship. However, this was not her research expertise, and the new position did not come with a pay raise or a seat on the faculty. Regardless of the lack of recognition for her expertise and accomplishments, Derick continued teaching and pioneering in her field. She introduced a course “Evolution and Genetics”, the first of its kind in Canada. In this way, she helped science at McGill become increasingly cutting-edge and relevant. The Molson family funded the creation of a new Chair in Genetics and an independent Department of Genetics in 1934.

Legacy

Upon her retirement in 1929, Derick became the first female professor emeritus in Canada. Carrie Derick was recognised for her contributions to science by her contemporaries and continues to be celebrated for her impressive career. McGill continues to honour her time and commitment to scientific excellence through the Carrie M. Derick Award for Graduate Supervision and Teaching, which recognizes outstanding contributions from faculty members in promoting graduate student excellence.

Beyond her academic work, Derick was a leader in early feminism in Canada and advocate for women’s right to education, work, suffrage, and birth control. She was an active member of numerous associations concerned with science, public health, women’s rights, and education.

Derick has also been honoured as a National Historic Person by the Government of Canada for her “outstanding contribution to science in both the academic and popular spheres.” In celebration of her 155th birthday in 2017, she was recognized with a Google Doodle in Canada, calling her “a true pioneer and visionary.”

Hidden gems: McGill’s early biological research and teaching aids

1885-1920

As biological science programs and their physical spaces expanded, research and teaching resources developed to further enhance hands-on learning.

The mystery of McGill’s Botanical Gardens

Not much is known about McGill’s Botanical Gardens, but they were a part of McGill’s biological teaching and research landscape at the turn of the century. Plans for the creation of the Botanical Gardens began in 1885, with the appointment of David Penhallow as Director of the Montreal Botanic Garden Association. However, the Association ceased work at the end of its second year due to an inability to secure a suitable site. Then in 1890, there is evidence that McGill University leased nine acres on Cote des Neiges just south of The Boulevard in Westmount, and with the help of Penhallow, finally organized a Botanical Garden. There were several conservatories, including a camellia house, a greenhouse, and an Australian house. Plants from around the world were housed in the greenhouses, including a somewhat extensive representation of Australasian plants. The 1899 Old McGill Yearbook describes the McGill Botanical Garden as occupying, “a commanding situation at the summit of the Cote des Neiges Hill, distant from the College about one and one-half miles, and comprises an area of about nine acres.” The Gardens were used by McGill students, especially during the winter, for botanical study, as well as by the general public for free. It appears that the Gardens ceased to exist around 1901 with no further mentions of its use or even its closure in the historical record.

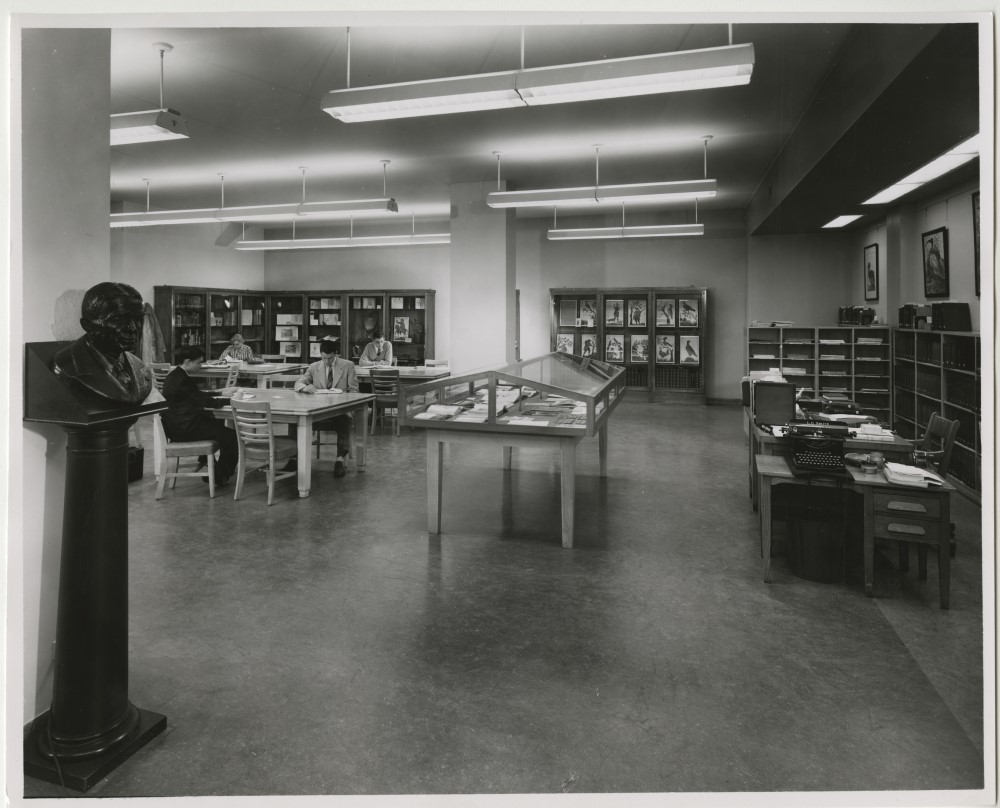

Blacker-Wood Collection in Zoology and Ornithology

Once an important research and teaching resource for the biological sciences, the Blacker-Wood Collection in Zoology and Ornithology is now part of the McGill Library’s Rare Books and Special Collections. This collection contains over 14 metres of records consisting of unpublished manuscripts and letters, painting and drawings, books, and artifacts. This historical collection, started in 1920, was once one of the principal research collections in zoology in North America.

The collection originated from the work of Casey Albert Wood, a McGill graduate and successful ophthalmologist whose research extended to the history of ophthalmology, comparative ophthalmology, and ornithology, and ultimately became a passion for collecting books and other materials on these subjects. In 1920, he founded the Blacker-Wood Collection at McGill as an ornithology library with a supporting collection in vertebrate zoology. The focus of the library gradually came to incorporate all aspects of zoology except entomology. Between 1920 and his death in 1942, Wood travelled extensively acquiring materials for the library.

Some highlights of the collection include the Ivanow collection of Persian, Arabic, and Urdu manuscripts; the Gurney reprints on crustacea; the archives of the Montreal Natural History Society; rare manuscripts on zoology; annotated typescripts; galley proofs; letters from 19th and 20th century naturalists; research and lecture notes; and over 10,000 paintings and drawings of animals. The collection heavily represents the Philippines and other regions of South East Asia and the South Pacific, but also contains content concerning North and Central America, and other regions. The collection also includes the Feather Book of Dionisio Minaggio, which is made entirely from the skins and feathers of birds.

Industry takes root: The Pulp and Paper Research Institute

1927-1946

A highly dynamic and productive research and educational institution, the Pulp and Paper Research Institute began McGill’s link to cooperative industrial research.

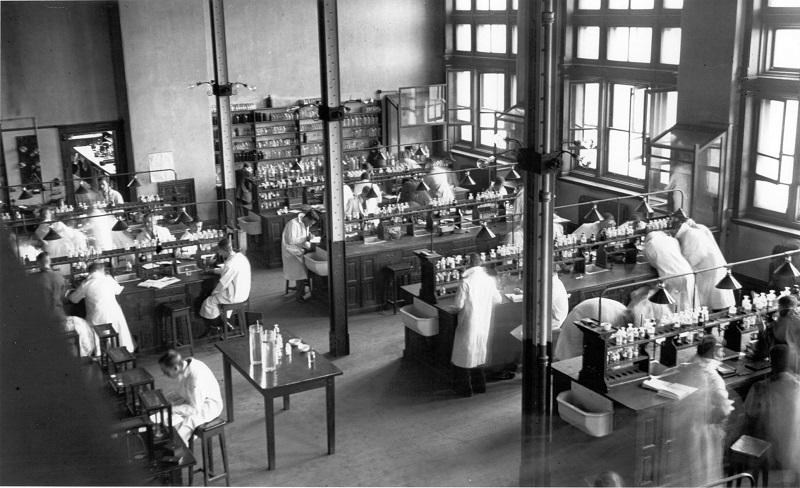

Reflecting a larger trend in society and science, the creation of the Pulp and Paper Research Institute at McGill in 1927 marked a turn towards industry and the creation of close links between chemistry research and important practical innovation. As a highly dynamic and productive research and educational institution, the Institute exists to train highly qualified personnel, conduct research, and disseminate technical information.

Originally the Institute consisted of the Cellulose Chemistry Department of McGill, the Pulp and Paper Division of the government’s Forest Products Laboratories, and the research labs of the Pulp and Paper Association. All this initial research activity was aimed at the study of wood fibres and expanded to study all aspects from the growing seedling in the forest to the production of finished pulp and paper. The building had large pulp mills and other mechanical equipment installed. Funding was plentiful and backed cooperatively both by industry and the government. This reflects the desire to make scientific research useful and have industrial applications in the early twentieth century.

What distinguished the Institute was the cooperative nature of its industrial research. By the mid-century, researchers were not compartmentalised and instead worked as teams on a project or a task-force basis. Teams included researchers and technicians from any of the Institute’s departments. Furthermore, the Institute participated greatly in postgraduate training, but did not restrict work and previous training to the pulp and paper industry. This left graduates equally prepared to enter any industry and often led to fruitful work.

Many significant researchers and graduate students benefited from the unique model of the Institute. William Chalmers, a McGill alumnus, contributed to the creation of plexiglass in 1930. As well, the manufacture of artificial vanilla, vanillin, was discovered while studying lignin. The Institute brought many successful scientists to campus such as Harold Hibbert, Clifford Purves, and Stanley Mason , strongly enhancing McGill’s research reputation.

Stanley G. Mason (1914-1987), father of microrheology: A native Montrealer, Stanley Mason received his PhD in physical chemistry from McGill University in 1939. He worked for the Department of National Defense and the Atomic Energy Division of the National Research Council before returning to McGill in 1946 as a professor in the Department of Chemistry and a member of the Pulp and Paper Research Institute. He was Director of the Applied Chemistry Division of the Pulp and Paper Institute until his retirement in 1978, named Otto Maas Professor in Chemistry in 1979, and achieved the status of Professor Emeritus in 1985. During his time at McGill, Mason supervised over 60 PhD students and published over 270 publications.

Mason and his students revolutionized the understanding of flowing suspensions and dispersions. He coined the term “microrheology” to describe a new theoretical framework with wide applications. While the context of his research was the pulp and paper industry, the results of his work on microrheology and wetting found applications in medicine, meteorology, and environmental science as well. His research gained him an international reputation and many honours throughout his career culminating with the Prix Marie-Victorin in 1986 (the highest scientific distinction in Quebec). As well, the biannual award of the Canadian Society of Rheology is named in Mason’s honour.

The Institute prided itself on its ability to conduct innovative research in industry without robbing universities of the services of their first-class specialists. It was the liaison between basic research with practical application which made the Institute so effective and allowed industry support to grow despite economic hardship. The Pulp and Paper Building continues its work today and still shares its space between the Department of Chemistry and the Department of Chemical Engineering.

A new science of the mind: From philosophy to psychology

1910-1948

As one of the oldest psychology departments in Canada, McGill’s Department of Psychology grew from its introspective roots into an experimental intellectual powerhouse during the twentieth century.

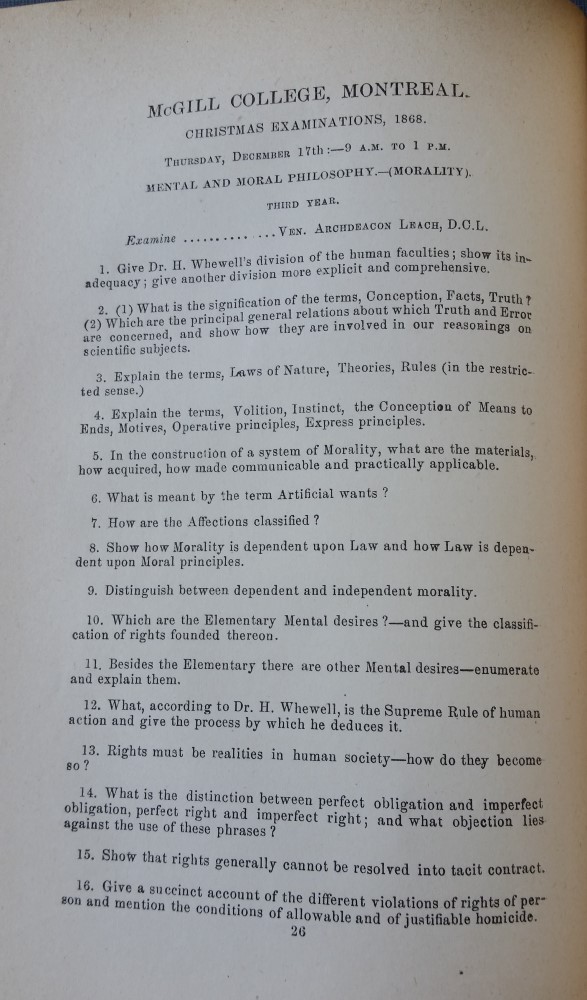

The Department of Psychology at McGill University is one of the oldest in Canada with the first psychology course being taught in 1850 by Dr. W. T. Leach. Psychology however originated in the Department of Philosophy and was then known as “Mental Philosophy”.

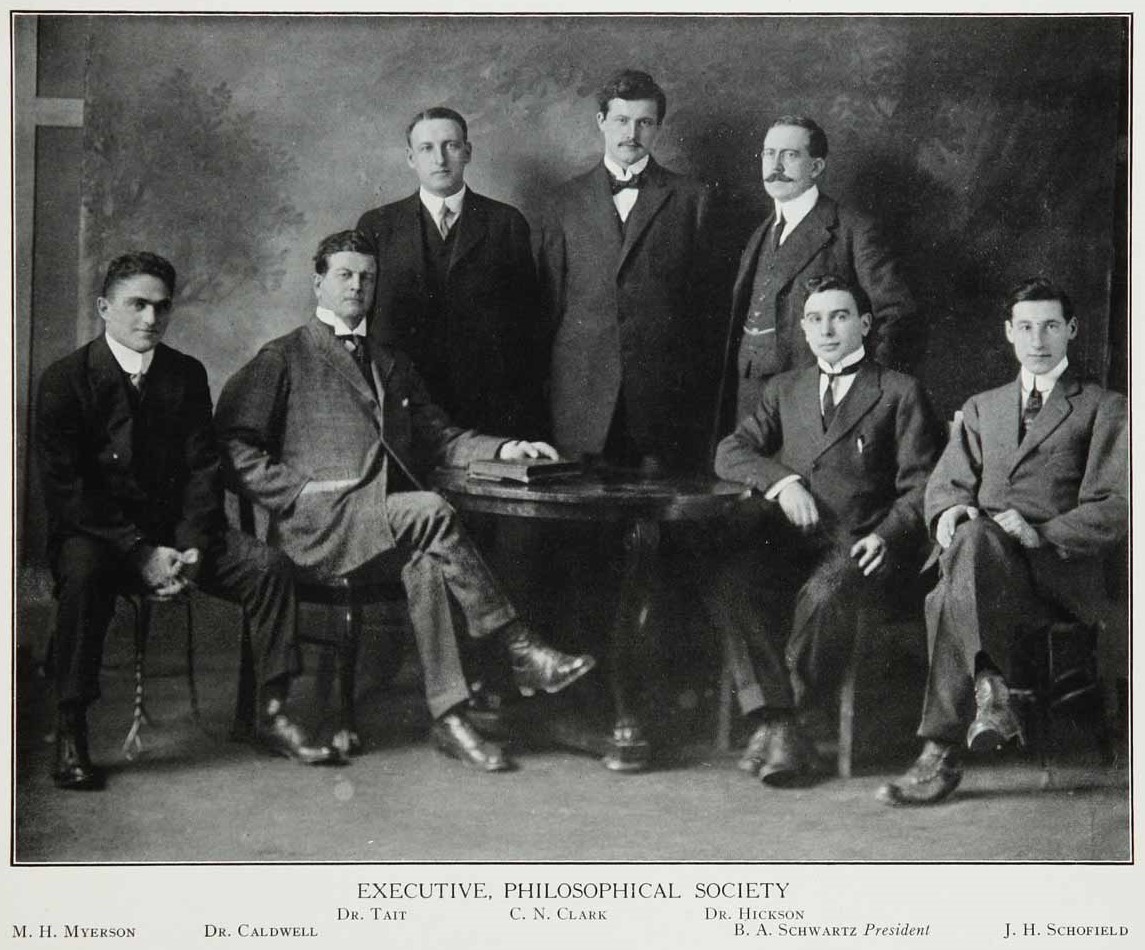

Late nineteenth century philosophers and psychologists did not differ on questions asked about the mind; both were concerned with sensation, perception, cognition, affection, and volition, all the makings of modern psychology. The difference of the emerging field of psychology and its home in Mental and Moral Philosophy was a shift in method to value the experimental method rather than introspection and observation. Under the stewardship of John Clark Murray, the department became increasingly equal between philosophy and psychology, thereby laying the groundwork for the rise of experimental psychology in the early twentieth century.

In the first decade of the twentieth century, more psychology classes were added and each year curriculum changes were continually made, bringing many familiar subdisciplines of psychology to McGill, such as child psychology in 1908. In 1905, J.W.A. Hickson became the first officially titled professor of psychology appointed at McGill. In these years it also became possible to study for an Honours degree and a Master’s degree in psychology. By 1909 the psychology curriculum in the Department of Mental and Moral Philosophy had expanded and differentiated so much as to require the hiring of an experimental psychologist, Dr. William Dunlop Tait.

The appointment of Tait led directly to the establishment of McGill’s first Psychological Laboratory in 1910, only the second of its kind in Canada. The lab was said to occupy eighteen rooms in the Arts Building.

The Psychological Laboratory occupies rooms in the Arts Building. In the main library are found the chief periodicals and works of reference on all branches of the science. Besides this, there has been added during the past year a considerable amount of apparatus so that the laboratory is now equipped for original research work in experimental psychology, physiological psychology, and applied psychology. The same equipment also serves to train students in the methods of experimental psychology, and furnishes material for demonstrations and lectures. (From History of Academic Psychology in Canada, 1982, p. 41)

By the 1920s students taking psychology quickly came to outnumber those pursuing philosophy in the shared department. Eventually the differences between philosophy and psychology, as well as vast personal differences between the individual scholars in the department, necessitated their separation and the Department of Psychology was officially founded in 1922. Now in a separate department, professors Tait and Kellogg rapidly developed graduate work and the department awarded its first PhD in 1933. The initial Ph.D. programme involved knowledge of advanced statistical methods and the ability to design and construct simple experimental apparatuses.

From the 1920s psychology was taught mostly as an applied discipline, with courses oriented towards psychology in the context of business and education. In 1939 the department also became concerned with applying their work on psychological testing to contribute to the war effort. By 1946 with the appointment of Robert B. MacLeod as Chair, the department reoriented towards a more theoretic, scientific concept of psychology with a strong focus on experimentation.

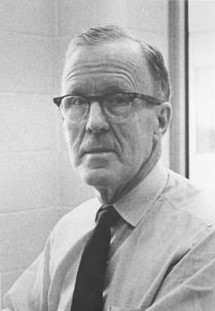

1948 marked the largest shift in the development of psychology at McGill with the appointment of Donald Olding Hebb as Chair. Hebb’s chairmanship initiated a period of growth with both increased undergraduate and graduate enrolment, staff size, research productivity, and the Department’s reputation within and beyond the university. Under Hebb, many of the twentieth century’s most notable psychologists and researchers came to McGill including Drs. Dalbir Bindra, Virginia Douglas, Wallace “Wally” Lambert, Ronald Melzack, Brenda Milner, Peter Milner, and James Olds.

Donald Olding Hebb (1904-1985) is often considered the “father of neuropsychology” because of the way that he was able to bring together neuroscience and psychology. This achievement was accomplished largely through his work The Organization of Behavior: A Neuropsychological Theory which was published in 1949. In this book, Hebb proposes that learning depends on the strengthening of synaptic links between assemblies of co-activated neural cells. This core principle of Hebbian Theory, which is often paraphrased as “Neurons that fire together wire together”, had a profound influence in Psychology, Neuroscience, and Artificial Intelligence.

Image Gallery

Click on the photos to advance through the slideshow.

[rev_slider alias=”science-era-2″][/rev_slider]