While the Faculty of Science as we know it only solidified in 1971, its origins date back to the foundation of McGill University. Scientific education and research always occupied an important space at McGill, but nineteenth-century understandings of the place of science in university education looked very different. In fact, until 1931, science classes were taught under the auspices of the Faculty of Arts and it was not until 1971 that Science became its own distinct faculty.

This period laid the foundations for many of the departments that are now part of the Faculty of Science. Moreover, this period is characterized by the diversification of scientific research and instruction and a gradually changing student body, and it ultimately provided the basis for future growth and innovation.

In this period:

- Origins of the institution

- The beginnings of scientific education

- Early pioneers

- William Dawson

- The roots of scientific research

- Anne Molson and classes for women

- Image Gallery

Origins of the institution

1801-1852

Royal Institution for the Advancement of Learning and James McGill

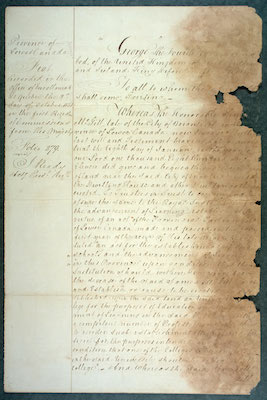

The origins of McGill University date back to 1801 with the creation of the Royal Institution for the Advancement of Learning (RIAL) by the Legislative Assembly of Lower Canada with An Act for the establishment of Free Schools and the Advancement of Learning in this Province. Twenty years passed before this legislation resulted in a degree-granting university. However, in 1813, James McGill, a prominent fur trader and merchant of Montreal, entrusted a significant portion of his fortune to the fledgling institution, bringing it a step closer.

James McGill’s legacy made possible the foundation of the university that bears his name. He also owned enslaved people, a fact our University acknowledges and that calls for our greater study and scrutiny.

By 1821, eight years after James McGill’s endowment, the RIAL received the Royal Charter from King George IV of England. This finally granted the new institution — now known as McGill College — the ability to grant degrees. In 1852, a further Royal Charter, granted by Queen Victoria of England, brought the RIAL and the Governors of McGill College to form one Board of Governors, creating a more modern governance structure.

The beginnings of scientific education

1843-1860

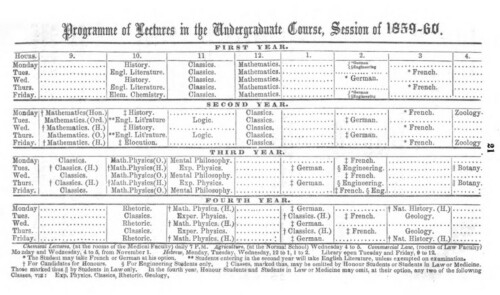

Scientific education, outside of the Faculty of Medicine, formally began when the Faculty of Arts started teaching classes in 1843. At this time, a general education was valued and, consequently, students at McGill were required to take a wide variety of classes in both humanities and sciences to attain their Bachelor of Arts. This training would equip students for careers in either discipline, as in the mid-nineteenth century humanities and sciences were not considered as distinct as they are now.

The 1856 Course Calendar describes the undergraduate program in Arts as, “a very thorough Classical and Mathematical Training, with adequate provision for the study of Logic, Mental and Moral Science, Natural Science and Modern Literature.” Upper–year students took courses in rhetoric and classics, as well as experimental physics, zoology and botany and mental philosophy, which incorporated psychology, logic and metaphysics. William Dawson, who was Principal at the time, emphasized the importance of scientific education for all students, implementing and teaching a mandatory natural history class beginning in 1856. Dawson himself taught many of these classes, as he appointed himself as a Professor of Natural History, Chemistry and Agriculture.

Like now, classes began in September and finished at the end of April, with a winter break. Students in the Faculty of Arts would have taken classes in what is now the Arts Building and in the original Burnside Hall, which was Dawson’s residence. Students were required to take subject matter exams upon entry to the university, as well as during each semester, both in oral and written forms. To be admitted, they were required to be proficient in mathematics as well as Latin, Greek and classics. Unlike now, students had the option to board with professors.

Early pioneers

1850-1870

While the Faculty of Arts began teaching classes in 1843, it would still be many years until it solidified into a cohesive faculty. In the 1840s, McGill campus was a jumble of buildings with limited teaching and research capacities. This began to change in 1853 with the appointment of the first Dean of Arts, William Turnbull Leach. Leach was a licensed minister, born in England and educated at the University of Edinburgh, who served as the Dean of Arts until his death in 1886. The most significant shift came as a result of hiring a young scientist from Nova Scotia, William Dawson, as the Principal of the university. Appointed in 1855, Dawson would go on to be the longest serving Principal of McGill, only retiring in 1893. During his tenure he oversaw wide–reaching changes at the university, particularly in the areas of scientific education and research.

During his time at McGill, Dawson coordinated the transition of McGill from a small, fragmented college, into a venerable university noted for its research and education. Dawson used his own money to lay pathways and plant trees, while implementing many administrative and educational changes. He demonstrated a deep commitment to the improvement of science and engineering education at McGill. The Faculty of Science would not be created for over one hundred years, meaning that all students interested in scientific studies studied in the Faculty of Arts.

As the course options increased, so did the need for professors, leading to the hiring of some notable scientists. One such scientist was Thomas Sterry Hunt, who taught Applied Chemistry and Mineralogy at McGill. He was a pioneer in the field of geochemistry in North America and was noted for his work on the geology of petroleum. He is also known as the inventor of the green dye used in American dollar bills. Around the same time, Charles Smallwood was appointed as an Honorary Professor of Meteorology. Although he did not have a degree in Meteorology, he had been taking meteorological measurements every six hours at his home for almost 20 years. When he became a professor at McGill, he brought his meteorological measurement equipment with him, establishing what would become the McGill Observatory.

By the 1860s, scientific education was solidified as an important aspect of education at McGill, and this was a time of significant expansion. Although he certainly did not work alone, Dawson can be credited for prioritizing science within this growing institution and putting in place measures that would flourish in years to come.

William Dawson

1820-1893

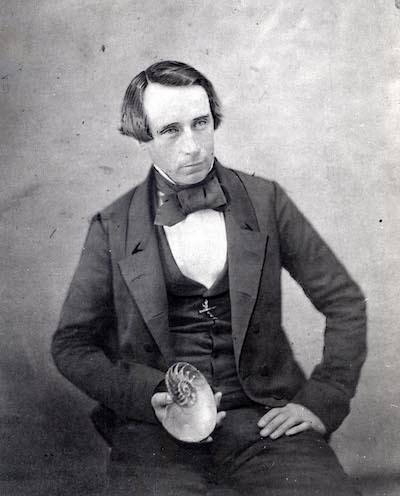

Education and early career

Born John William Dawson on October 13, 1820 in Pictou, Nova Scotia, he received his education in Pictou and then proceeded to study natural science at the University of Edinburgh. He completed his degree in 1847 and returned to Nova Scotia. Dawson was trained as a geological surveyor and worked for the government of Nova Scotia but remained devoted to education. He taught at the Pictou Academy and Dalhousie College and in 1850, he was appointed Nova Scotia’s first superintendent of Education. As part of this position Dawson traveled throughout Nova Scotia, allowing him to explore the province’s geology. During this time, he discovered the oldest known reptile in the history of life, which he named Hylonomous Lyelli in honour of his mentor and prominent geologist, Sir Charles Lyell. At the beginning of Dawson’s career, he cultivated both his commitment to education and to scientific inquiry.

McGill years

In 1855, Dawson was appointed McGill’s fifth principal. During his tenure as Principal, he did not abandon his scientific interests. He continued to undertake research on the natural history of Eastern Canada. In 1859, he published a seminal paper on the first fossil plant, Psilophyton princeps, found in rocks from the Devonian period, a geologic period that took place between 419.2 million and 358.9 million years ago. Initially, the significance of this discovery was not recognized, but now Dawson is considered as one of the founders of paleobotany — the science of fossil plants. He served as the president of the Montreal Natural History Society in 1857 and as the first president of the Royal Society of Canada from 1882 to 1883. In recognition of his contributions to natural history, a mineral discovered during the construction of the Redpath Museum in a feldspathic dike was named Dawsonite in his honour.

Legacy

Beyond his employment at McGill, Dawson worked for the Canadian Geological Survey, where he studied the Silurian, Devonian and Carboniferous rocks of Canada, gaining insight into the early forms of life on earth. Dawson actively engaged in the great scientific debates of his time. A devout Christian, he spoke out against Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution in multiple articles, arguing that humans made their appearance in the recent past. While the present-day scientific consensus shows that Dawson was incorrect, his participation in the debate around evolution demonstrates that he was a notable figure in the scientific community at the time. When Dawson retired from McGill in 1893 after 38 years of service, the longest tenure of any McGill Principal to this day, he left a legacy of both scientific and academic advancement.

The roots of scientific research

1870-1890

As scientific education expanded through the 1850s and 1860s, the need for dedicated teaching positions and laboratories grew. Enabled by donations from some of the university’s benefactors, Chairs in multiple scientific disciplines were established at the beginning of the 1870s. These Chairs, and later laboratories, would serve as the precursors to the departments that exist today.

One of the first major donations was made in 1871, by William Logan, a Canadian geologist who donated $20,000 to the university to create the Logan Chair in Geology. This position was initially held by William Dawson, while he also held the Principalship of the university. At the same time, significant donations from Peter Redpath and the Frothingham family allowed for the creation of Chairs in Natural Philosophy and Moral Philosophy, the embryonic forms of the Departments of Physics and Psychology respectively.

This expansion continued into the 1880s, with the creation of a Chair in Botany in 1882 and a new Chemistry Lab in 1884. The Chair in Botany was, in part, created to help lighten the teaching load of William Dawson. David Penhallow, an American paleobotanist, was appointed to fill the vacancy. His studies focused on the anatomy and physiology of plants. Before he was appointed at McGill, he helped establish the Imperial College of Agriculture in Sapporo, Japan. During his tenure he became a leading authority on fossil plants from the Cretaceous, Paleogene and Neogene periods, spanning from 145 million years ago to 2.6 million years ago. He prioritized the study of the internal structures of plants over their external form and was one of the first to interpret the evolutionary sequence of conifers in physiological terms. He was the President of the Botanical Society of America from 1888-1892, and of the Natural History Society of Montreal in 1902. Penhallow is remembered for pioneering newer forms of botanical study when older morphological approaches were still the main forms of inquiry. His hiring exemplifies the growth and diversification of scientific education at McGill that took place in the 1880s.

Science continued to branch off at McGill during the 1890s, this time in mathematics and physics. Until 1891, physics and mathematics were housed together, under the Department of Mathematics and Natural Philosophy. In 1891, a generous donation from William MacDonald, a successful tobacco manufacturer, endowed a Chair in Experimental Physics and enabled the creation of a Physics Lab that was the predecessor of the Department of Physics. MacDonald’s donation of $800,000 also financed the creation of two new science buildings at McGill, the MacDonald Physics Building and the MacDonald Chemistry and Mining Building. The MacDonald Physics building was constructed in 1893 to enable more experimental physics research at McGill. The edifice contained multiple labs and new pieces of equipment to study electricity, light, lead and the elements. It was built entirely out of wood, masonry and copper, with bronze and brass for nails and fixtures. No iron or steel was used in its construction to minimize magnetic interference that could negatively affect experiments. It was in this building that Ernest Rutherford, among many other physicists, performed his experiments. Soon after, in 1897, the MacDonald Chemistry and Mining Building was built. When it first opened, Metallurgy and Mining Labs were housed in the two basement floors, while the rest of the building housed chemistry and geology laboratories, all considered to be related fields at the time. By the end of the 19th century, science at McGill had expanded to encompass a diversity of fields and disciplines, with the infrastructure and financing to enable cutting–edge scientific research at the turn of the century.

Anne Molson and classes for women

1864-1885

It is well known that women began formal classes at McGill in 1884. However, the path to co-ed integration at McGill has interesting and often overlooked links to the modern Faculty of Science.

The Montreal Ladies’ Educational Association (1871-1885)

In the 1870s, well before women could receive degrees from McGill University, wealthy Montreal women attended university-level lectures under the auspices of the Montreal Ladies’ Educational Association.

During a visit to Britain during the summer of 1870, Principal John William Dawson and his wife collected information on higher education for women. Upon returning to Montreal, they drafted a detailed proposal and appealed to the city’s most prominent families for support in creating educational opportunities for women. On May 10, 1871, many of the leading English-speaking bourgeoisie gathered in the Molson home to officially form the Montreal Ladies’ Educational Association. Anne Molson was voted the association’s first president, and her husband was made treasurer. All members and officers of the association were women, except for the role of treasurer, which had to be held by a man.

According to Dawson’s papers, the goal of the Association was to create “lectures on Literary, Scientific, and Historical subjects for the higher education of women, and eventually, if possible, the establishment of a College for Ladies in connection with the university.” Women were able to attend classes as either students or auditors, optionally completing assignments and sitting exams. The Association also attempted to award certificates to women who successfully passed three years of classes. Although completely separate from the university, the coursework was equivalent to that of the men earning degrees at McGill and was taught by the same professors.

The first session (1871-1872) included twenty lectures on Mineralogy (Useful and Ornamental Stones) by Principal Dawson and Chemical and Physical Geology by Dr. Sterry Hunt. Although intended to be strictly academic, practical courses were added to the available classes. During its fourteen years of existence, the Association provided lectures covering a wide variety of topics including French literature, English language and literature, natural philosophy, astronomy, logic, chemistry, physiology, electricity and magnetism, architecture, light, nutrition, cooking, domestic surgery, and nursing.

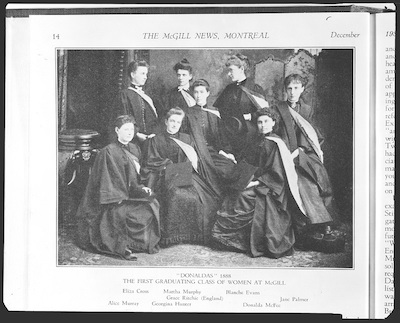

Principal Dawson also asked the Association to assist him in setting up classes for women at McGill to earn degrees. However, a sizable and unprompted donation by Sir Donald Smith rendered the continued existence of the Montreal Ladies’ Educational Association unnecessary and shortly thereafter women were finally able to begin degree-granting classes at McGill in 1884. During its fourteen–year existence, the Montreal Ladies’ Educational Association made significant strides in providing quality, university-level education for women at a time when it was undervalued and, most importantly, proved that higher education for women was possible at McGill. To cap this achievement off, a former member of the Association, Miss Georgina Hunter, joined the first class of women at McGill University.

The Donaldas

Donald A. Smith, later Lord Strathcona, gave McGill a $120,000 endowment “on condition that the standard of education for women should be the same as that for men for the ordinary degrees in Arts, that the degrees to be granted to women should be those B.A., M.A., L.L.D., which should be so granted to them by McGill University on the same conditions as to men.” To honour Smith’s generous gift, female students at McGill were known as Donaldas for many decades.

This gift funded the creation of Royal Victoria College. Built in 1899, the first wing contained eight classrooms, an assembly hall for 700 students, a dining hall, reading and drawing rooms, as well as housing for a warden, tutors, and the first fifty-two female students of the College.

As students in the Faculty of Arts, women could take classes in English literature, history, German, French, Botany, Zoology, Experimental Physics and Natural and Mental Philosophy. These women continued to be educated separately from male students, but finally could earn the same degrees as men.

Anne Molson Gold Medal

Anne Molson came from a prominent anglophone Montreal family. Education was one of her philanthropic interests, especially for young women like her daughters. In 1864 she proposed to Principal Dawson, a good family friend, the donation of a medal to McGill University. He recommended this medal be awarded to the best student in physics, mathematics, and physical science. Despite the potential irony of donating a medal to a university that did not admit women at the time, Anne Molson continued to work towards providing university-level education for women and in fact during her lifetime, the medal bearing her name was awarded to a woman for the first time. In 1898, only thirteen years after women could enroll at McGill, Harriet Brooks received the honour. The award still bears Anne Molson’s name and continues to be awarded to the top student in the department. Its past winners have included many notable scientists and educators, including Harriet Brooks and Anna McPherson.

Image Gallery

Click on the photos to advance through the slideshow.

[rev_slider alias=”science-era1-photos”][/rev_slider]