This period, 1914 to 1938, was one of upheaval and modernization for McGill’s Faculty of Law, as it was for the whole world. In 1914, Annie MacDonald Langstaff became the first woman to earn a law degree from McGill. Langstaff’s graduation shaped the coming decades, inspiring increasing numbers of women to attain law degrees, to fight for women’s rights and to attain access to the Quebec Bar. The same year saw the outbreak of World War I, which also left its mark on the Faculty. McGill Law lost many young students, such as Angus Splicer, the Faculty’s first known Indigenous student. The War also led to great social change, and it was during the post-War years that the Faculty became home to numerous veterans, women, and McGill Law’s first known Black students. This period was also one of pedagogical innovation, with the Dean, Robert Lee, introducing the LL.B. and LL.M. programmes in 1917-1918. These experiments were controversial and short-lived, ending less than a decade later, but initiated a move to bijural education that has become integral to the Faculty of Law’s identity to this day.

In this period:

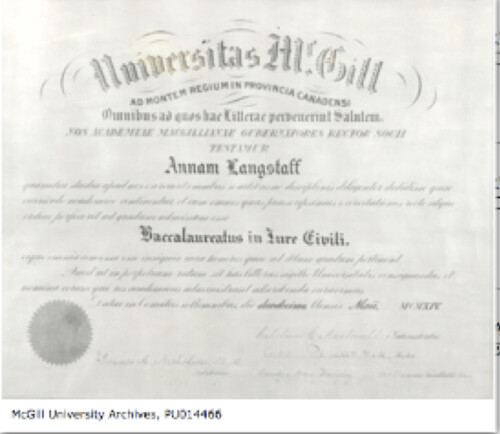

Annie MacDonald Langstaff, First Woman to Graduate from McGill Law

Annie MacDonald Langstaff (B.C.L. 1914) was the first woman to graduate from McGill Law; however, she was denied entry to the Quebec Bar because of her gender. With the help of the prominent Montreal lawyer Samuel Jacobs, she petitioned the Superior Court of Quebec to allow women access to the Bar. When she was unsuccessful, women’s groups and feminists spoke out against the Court’s decision. After decades of activism, women finally gained access to the Quebec Bar in 1941. Langstaff was never admitted because she did not have a Bachelor of Arts, a requirement at the time. Langstaff worked with Jacobs’s firm, became a talented aviatrix, published articles on family law, and wrote the first Quebec Legal Dictionary.

Annie MacDonald Langstaff (B.C.L. 1914) was the first woman to graduate from McGill Law; however, she was denied entry to the Quebec Bar because of her gender. With the help of the prominent Montreal lawyer Samuel Jacobs, she petitioned the Superior Court of Quebec to allow women access to the Bar. When she was unsuccessful, women’s groups and feminists spoke out against the Court’s decision. After decades of activism, women finally gained access to the Quebec Bar in 1941. Langstaff was never admitted because she did not have a Bachelor of Arts, a requirement at the time. Langstaff worked with Jacobs’s firm, became a talented aviatrix, published articles on family law, and wrote the first Quebec Legal Dictionary.

McGill’s Faculty of Law is now home to the Langstaff Seminar Room on the second floor of NCDH. In 2006, on the 65th anniversary of women’s entry into law, the Bar posthumously awarded her membership and a Medal of the Bar of Montreal. On the occasion, the Bâtonnière de Montréal, Me Julie Latour, BCL’86, LLB’86, who spearheaded this initiative, noted that while there remained progress to be made, Quebec had become the jurisdiction with the highest proportion of female lawyers in North America.

McGill’s Faculty of Law is now home to the Langstaff Seminar Room on the second floor of NCDH. In 2006, on the 65th anniversary of women’s entry into law, the Bar posthumously awarded her membership and a Medal of the Bar of Montreal. On the occasion, the Bâtonnière de Montréal, Me Julie Latour, BCL’86, LLB’86, who spearheaded this initiative, noted that while there remained progress to be made, Quebec had become the jurisdiction with the highest proportion of female lawyers in North America.

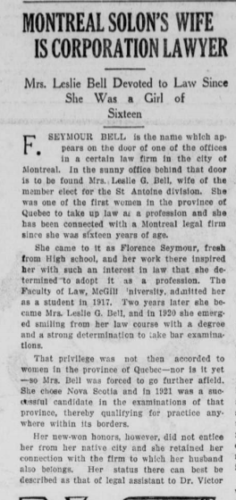

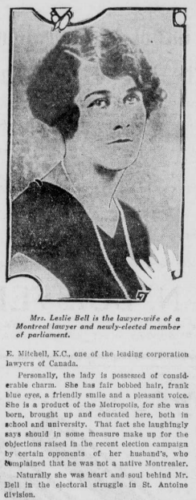

Florence Seymour Bell

Florence Seymour Bell, BCL 1920, was the second woman to graduate from McGill Law, alongside Mrs. W. Hughes, and the first woman to practice law in Quebec. As a woman, she was not allowed to join the Quebec Bar. However, she found a loophole by joining the Nova Scotia Bar and, using a reciprocity agreement between the provinces, to practice law in Quebec; however, as a woman, Bell was still barred from pleading before courts in Quebec, so she practiced corporate law instead. Many women, such as Elizabeth Monk, followed her in being admitted to other provinces’ bars in the years prior to 1941, when women were finally allowed entry to the Quebec Bar.

Bell played an important role in petitioning for women’s admission to the Bar in Quebec. She also served as Vice President of the National Association of Women Lawyers, President of the University Women’s Club of Montreal, and the Senior Commandant of the Women’s Volunteer Reserve Corps in the Second World War.

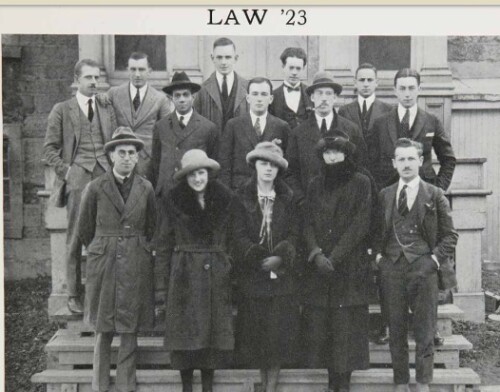

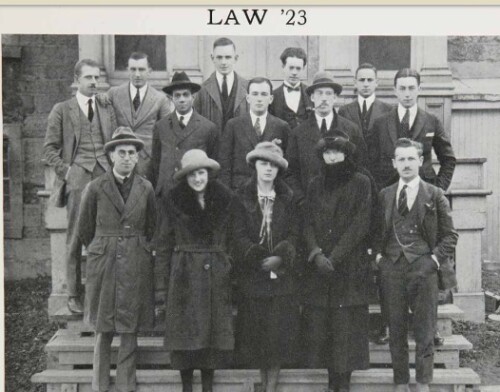

Women in the Class of 1923

A record number of women studied at the Faculty in 1923. Three of these “co-ed” students were Margaret McEwan Sim, Frances Douglas, and Elizabeth Monk, pictured above from left to right, each of whom received their degrees in 1923. Also at the Faculty at that time were Louise Weibel and Dorothy Heneker.

There are many firsts in this group of women. Heneker was the first to graduate with both the B.C.L (1925) and LL.B. (1924) degrees, Weibel was first to obtain an LL.M (1923), and Monk was first to win the Elizabeth Torrance Gold Medal. Many of the group went to be highly influential; their accomplishments are too numerous to be comprehensively detailed. Monk, for example, was also one of the first women to appear before the Superior Court of Quebec and was the first woman in Quebec named Queen’s Counsel. She also acted as legal counsel for the League for Women’s Rights and lobbied for women’s suffrage in Quebec. Heneker represented Canada in Geneva at the first international Conference of Business and Professional Women as president of the Club in Canada. Some of the others did not pursue legal careers, perhaps in part because the Langstaff decision made it so difficult for women to practice law in Quebec.

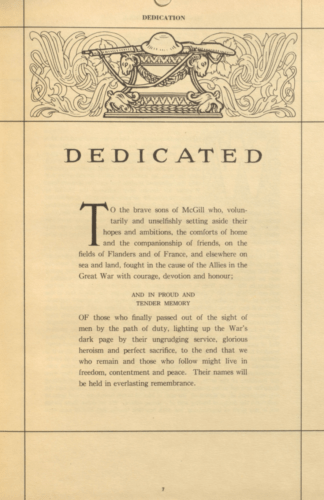

WWI: The War

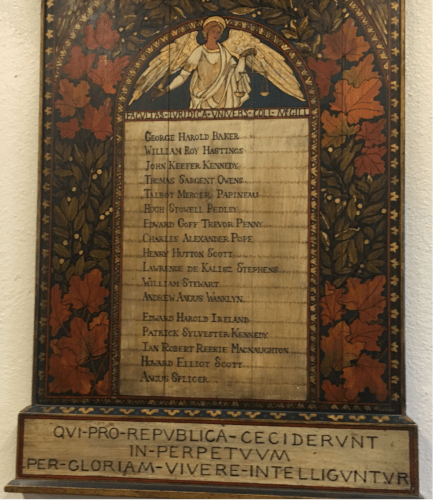

This dedication (left) was written in the World War I Honour Roll for McGill students and graduates who served in the War. Canada, as part of the British Empire, entered the war on August 4, 1914. Many McGill Law students served during the war; 20 Law students and graduates lost their lives in service or shortly thereafter.

A memorial (right) for deceased McGill Law students who served in World War I, painted by Dean Lee’s wife, still adorns the wall at the main entrance to Old Chancellor Day Hall.

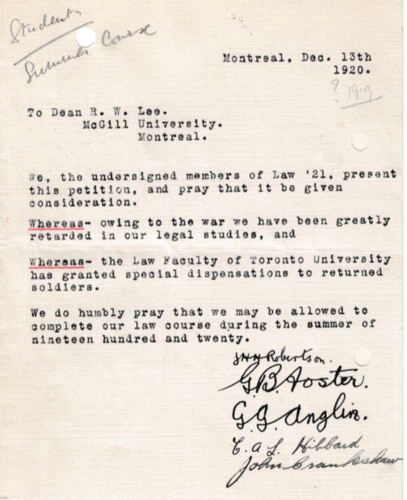

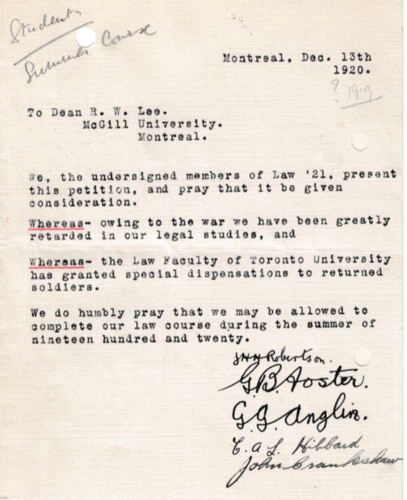

WWI: Veterans Return

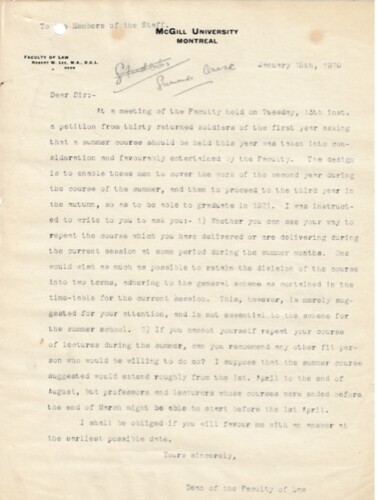

The First World War ended on November 11, 1918. Returning students presented several petitions asking to complete the law programme in one and a half years instead of three, given the time they had served (one example is reproduced above, left). These petitions proved successful, as the Faculty allowed the students to continue their studies over summer breaks. A letter from Dean Lee (D.C.L. 1917) is also reproduced above (right) to the members of the Faculty of Law regarding the proposed schedule. The class of returning soldiers would later become known as the Famous Class of Law ‘21, as it produced two federal Cabinet Ministers (Brooke Claxton and Douglas C. Abbott), several judges, the first Governor of the Bank of Canada (Graham F. Towers, although he never finished his law degree), a leader of the Montreal City Council (Winchester H. Biggar), approximately eight commanders of Montreal militia regiments, as well as many other prominent people.

Other initiatives were also put in place to ease veterans’ transition into legal life, including special entrance requirements for veterans. Consequently, in 1919, McGill Law counted 90 first year students—the highest ever recorded at the time. Military service in World War I was also deemed to be equivalent to clerking for the purposes of admission to the Quebec Bar.

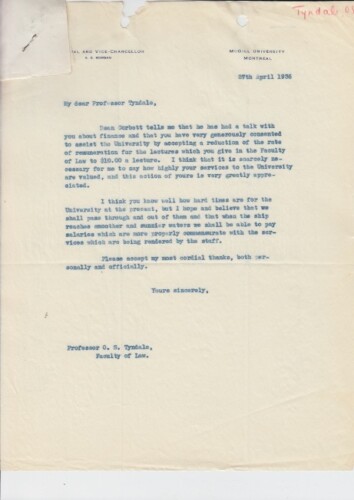

The Great Depression

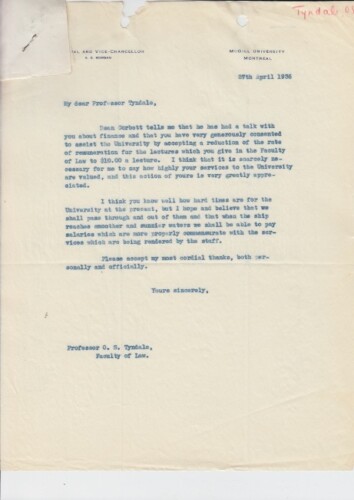

The Great Depression was a difficult period for the Faculty of Law and for McGill University as a whole. During this time, the University reduced salaries, left vacancies unfilled and raised student fees to alleviate its large deficits. For example, in this 1936 letter (left), Principal Morgan wrote that Professor Tyndale (B.C.L. 1915, D.C.L. 1947) of the Faculty of Law had agreed to reduce his salary to 10$ per lecture to help the University. Additionally, the economic depression resulted in fewer financial contributions to McGill from the public, which limited the Faculty of Law’s development plans.

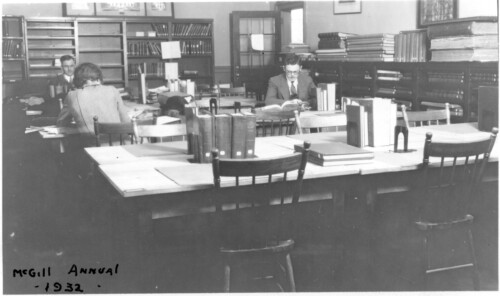

The photo on the left shows McGill Law students studying at the library in 1932. Throughout the Great Depression, students were studying law at McGill in an effort to secure better employment after their graduation. However, as Isabel G. Gales (B.C.L. 1936) recalled, “[t]here were few jobs available, though, and they did not pay very well.” One of the initiatives that responded to this was the 1932 program whereby each member of the Law Undergraduates’ Society contributed 50 cents to the Unemployment Relief Fund to assist McGill Law’s graduates who were struggling to find employment.

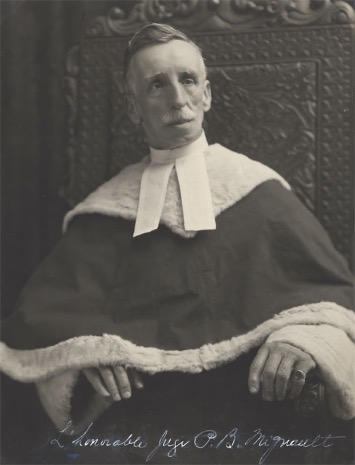

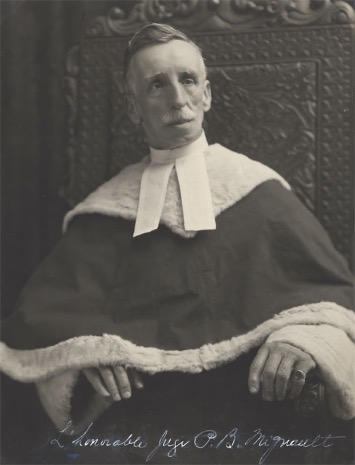

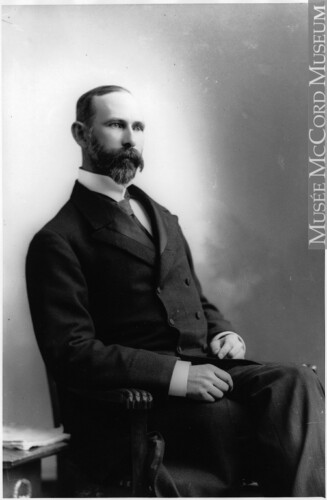

Pierre-Basile Mignault

Pierre-Basile Mignault (B.C.L. 1878, LL.D. 1920) was the second McGill Law graduate to sit on the Supreme Court of Canada. As a McGill student, he petitioned for a more regular course of study and won the Elizabeth Torrance Gold Medal. He returned to McGill to teach civil law from 1912–1918, and received an LL.D in 1920. In 1918, he joined the Supreme Court of Canada, where he became an outspoken defender of the civil law in Quebec, emphasizing the tradition’s distinctiveness and integrity. His legacy endures to this day in the Concours de plaidoirie Pierre-Basile-Mignault moot, and in the numerous works and cases that continue to cite him.

Pierre-Basile Mignault (B.C.L. 1878, LL.D. 1920) was the second McGill Law graduate to sit on the Supreme Court of Canada. As a McGill student, he petitioned for a more regular course of study and won the Elizabeth Torrance Gold Medal. He returned to McGill to teach civil law from 1912–1918, and received an LL.D in 1920. In 1918, he joined the Supreme Court of Canada, where he became an outspoken defender of the civil law in Quebec, emphasizing the tradition’s distinctiveness and integrity. His legacy endures to this day in the Concours de plaidoirie Pierre-Basile-Mignault moot, and in the numerous works and cases that continue to cite him.

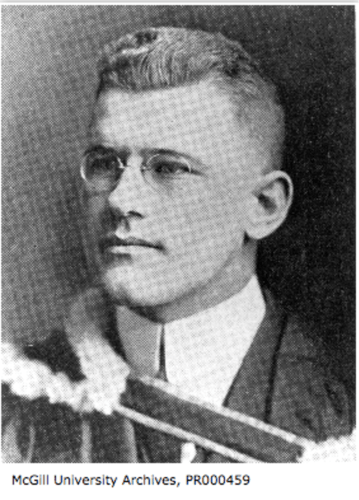

Dean Robert Warden Lee

Robert Warden Lee’s deanship (1915–1921) was marked by ambitious transformations in the Faculty. He hired the school’s first non-decanal full-time professors, H.A. Smith and Ira Mackay. Lee was the first Dean who had not been admitted to the Quebec Bar. Instead, he had been trained at Oxford and had been a career academic.

The Faculty under Lee offered a three-year B.C.L., a two-year LL.B., a one-year master’s degree, and a four-year dual degree. For Lee, these innovations were designed to expand the Faculty’s academic ambitions beyond one of “respectable mediocrity” as a purely provincial institution. These curricular reforms foreshadowed the National Programme that would be established in the 1960s, but they were ultimately short-lived. The following Dean, R.A.E. Greenshields, would abolish the common law (LL.B.) and masters programs in favour of a more scientific and practical approach to legal education.

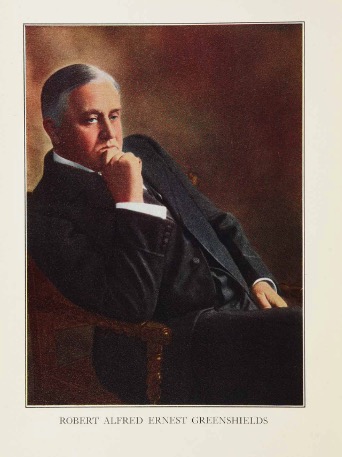

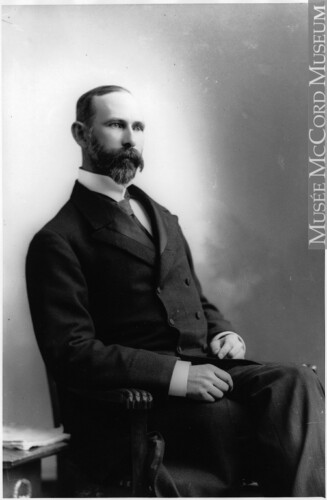

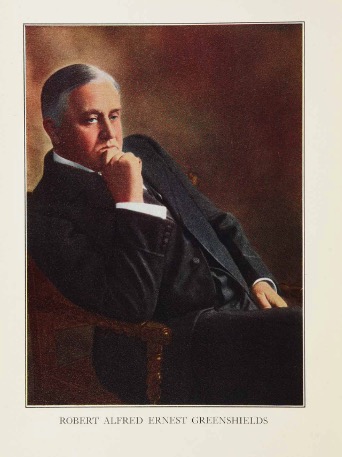

Dean Robert Alfred Greenshields

Robert Alfred Greenshields (B.C.L. 1885, LL.D. 1929) began his career by defending Louis Riel alongside his own brother, James Naismith Greenshields. Robert Greenshields specialized in criminal law after the trial and taught it at McGill. To this day, students with the highest standing in criminal law win the Chief Justice Greenshields prize. He became a Superior Court Judge in 1910 and was Dean of the Faculty from 1921–1928. As Dean, Greenshields made the law programme full-time, requiring students to attend classes throughout the day rather than just during mornings and evenings. He also abolished the LL.M. and LL.B. programs, arguing that McGill Law’s purpose was to teach the law as it was applied in Quebec. Students loved Greenshields’s wit and sarcasm, referring to him as a “great delight”, and once calling him at 3 AM to have him bail them out from jail after a rowdy law undergraduate dinner.

Robert Alfred Greenshields (B.C.L. 1885, LL.D. 1929) began his career by defending Louis Riel alongside his own brother, James Naismith Greenshields. Robert Greenshields specialized in criminal law after the trial and taught it at McGill. To this day, students with the highest standing in criminal law win the Chief Justice Greenshields prize. He became a Superior Court Judge in 1910 and was Dean of the Faculty from 1921–1928. As Dean, Greenshields made the law programme full-time, requiring students to attend classes throughout the day rather than just during mornings and evenings. He also abolished the LL.M. and LL.B. programs, arguing that McGill Law’s purpose was to teach the law as it was applied in Quebec. Students loved Greenshields’s wit and sarcasm, referring to him as a “great delight”, and once calling him at 3 AM to have him bail them out from jail after a rowdy law undergraduate dinner.

He became Chief Justice of Quebec in 1933, presided over the welcoming of women into the Quebec bar, and continued to work as a judge until the day before he died, at age 81. In 1952, his widow left a large endowment for entrance scholarships in his memory.

Dean Percy Corbett

Percy Corbett was Dean of McGill Law from 1928 to 1936 and an international law professor from 1928 to 1943. During his younger days, Corbett was awarded a Rhodes Scholarship just before the War. Nevertheless, in 1916, Corbett paid for his own passage to England in order to serve, after his Battalion was told it was not needed overseas and would be staying in Canada. Once there, he was wounded twice—once severely at the Somme—and received the Military Cross.

Percy Corbett was Dean of McGill Law from 1928 to 1936 and an international law professor from 1928 to 1943. During his younger days, Corbett was awarded a Rhodes Scholarship just before the War. Nevertheless, in 1916, Corbett paid for his own passage to England in order to serve, after his Battalion was told it was not needed overseas and would be staying in Canada. Once there, he was wounded twice—once severely at the Somme—and received the Military Cross.

As Dean, he emphasized the need for full-time professors, and hired F.R. Scott and John Humphrey as part of this project. Corbett viewed McGill as ideally situated for the study of international law. In his publications, he discussed the shaping of the post-War world, Canada’s legal relationship with England, and lasting world peace. In 1932, he instituted the M.C.L., a graduate level degree requiring a major written submission. He also imposed a writing requirement on undergraduate students, who were expected to write a 5,000 to 10,000-word thesis in order to graduate. Students revered Corbett but were often apprehensive about his Roman law and international law classes due to his intimidating intellect and his habit of teaching in Latin without giving translations.

After leaving McGill, he continued his career in the United States, the Netherlands, and India.

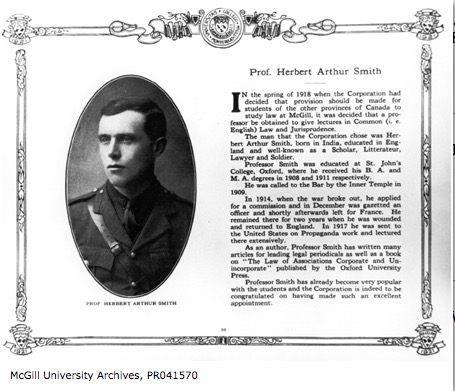

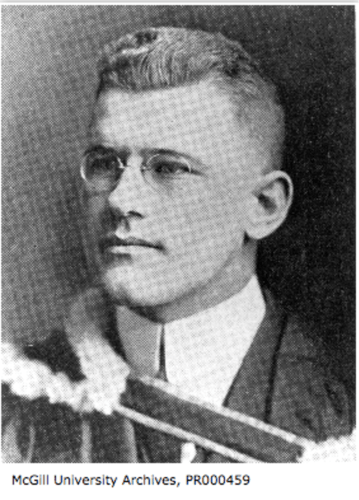

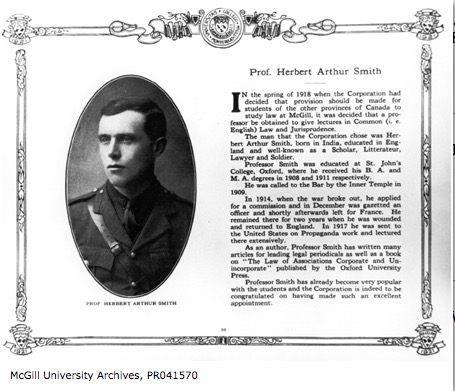

Herbert Arthur Smith: McGill’s First Common Law Professor

Herbert Arthur Smith was the first full-time non-decanal professor and the first professor of common law at McGill Law. Hired by Dean Robert Lee, his professorship marked the Faculty’s turn towards a more holistic curriculum. In addition to preparing legal professionals for practice in Quebec, the Faculty began to seek to provide an education that would equip students to work elsewhere in Canada and in a variety of different fields, including in the common law. Smith was keenly aware of the politics of teaching the common law in Quebec and sought to reassure others that his desire to make the Faculty not merely “provincial” was not a desire to expand the reach of the common law into Quebec. Still, he was never appointed Dean because many alumni and members of the McGill Board of Governors believed that his initiatives were detracting from the B.C.L. program.

Herbert Arthur Smith was the first full-time non-decanal professor and the first professor of common law at McGill Law. Hired by Dean Robert Lee, his professorship marked the Faculty’s turn towards a more holistic curriculum. In addition to preparing legal professionals for practice in Quebec, the Faculty began to seek to provide an education that would equip students to work elsewhere in Canada and in a variety of different fields, including in the common law. Smith was keenly aware of the politics of teaching the common law in Quebec and sought to reassure others that his desire to make the Faculty not merely “provincial” was not a desire to expand the reach of the common law into Quebec. Still, he was never appointed Dean because many alumni and members of the McGill Board of Governors believed that his initiatives were detracting from the B.C.L. program.

Smith was admired for his intelligence and idealism and was widely seen as a leader behind the scenes in the Faculty.

Angus Splicer: McGill Law’s First Known Indigenous Student

Angus Splicer is believed to be the first status Indian student to attend McGill Law. Splicer, a Mohawk from Kahnawake, transferred to McGill from Dartmouth College in 1915. Following the precedent established by status Indian students studying Medicine, Splicer applied to the Department of Indian Affairs for assistance with his school fees, which the Department agreed to provide on the condition that the university provide updates on Splicer’s progress. Splicer joined Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry in March 1915 after only one school year at McGill. In June 1916, he was declared missing, presumed dead. His name is inscribed on the Ypres Memorial in Belgium and he is also remembered at this memorial in Kahnawake (above right).

The scarf pictured above (left) is granted by the First Peoples’ House to Indigenous students upon graduation from McGill. Introduced in 2011, it was designed by Kahnawake designer Tammy Beauvais. The eagle feather is meant to recognize the recipient’s important achievement and the Hiawatha wampum belt, depicting the six nations of the Haudenosaunee, represents the Mohawk territory on which McGill sits.

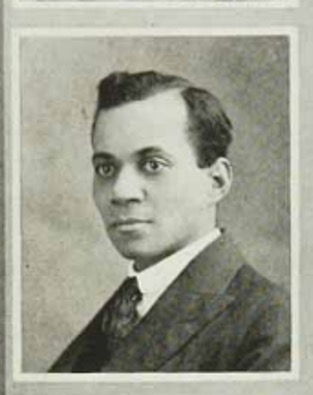

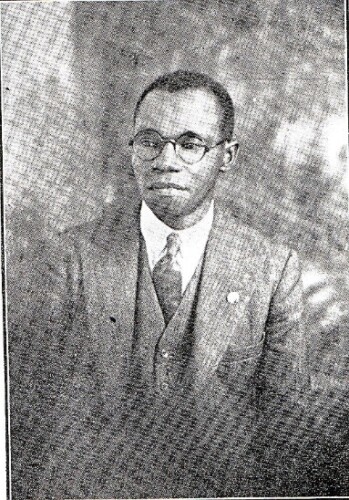

First Black Law Students at McGill

From 1919 to 1924, five Black students were enrolled at McGill Law: Gibson and John Edward Doston Carberry (LL.B. 1923) (left), as well as Talbert Allen Armstrong, Herbert R. Codrington, and Ethelred Erasmus Adolphus Campbell (right), who did not obtain degrees. This surge in Black student enrolment would not be repeated for decades: at the time, Black graduates would have been unable to practice law in Montreal.

John Edward Doston Carberry (LL.B. 1923) was one of the first Black students to graduate from McGill Law, along with Samuel Hersey Gibson (LL.B. 1922). After graduating, Carberry moved to Jamaica, where he eventually reached the position of Chief Justice of the Supreme Court.

While little is known about many of the other early Black McGill Law students, Ethelred Erasmus Adolphus Campbell was a successful chemist who discovered, among other things, how to extract oil from the pimento leaf. In 1924, he enrolled at McGill Law, but left when the LL.B. program was abolished. He then studied law in the United Kingdom, became a lawyer, and returned to Jamaica where he practiced law and became an influential politician.

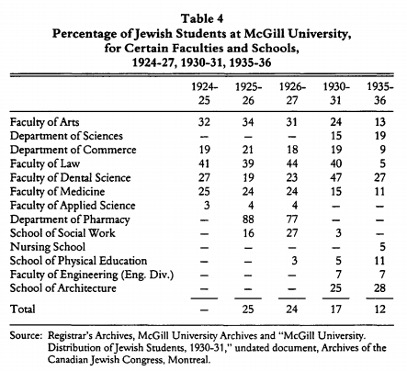

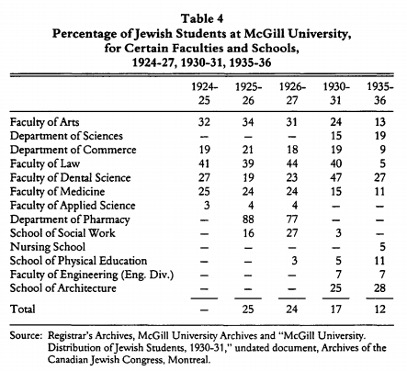

Jewish Students Face Barriers

In the 1930s, some McGill faculties established admissions quotas limiting the number of Jewish students. Although no formal quota was put in place for the Faculty of Law, the enrollment of Jewish students declined from 40% in the 1920s and early 1930s to 5% in 1935–1936. Despite being a significant demographic in the Quebec legal community, Jews continued to face barriers in the practice of law in Quebec throughout this period.

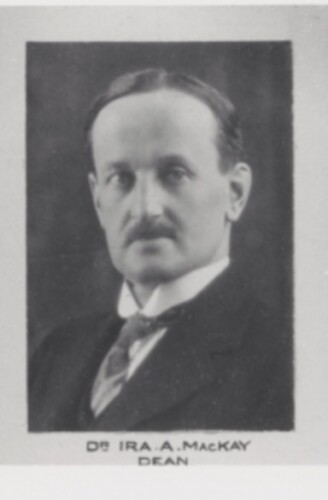

One proponent of the quota system was Ira MacKay, who taught at McGill Law from 1923 to 1925 before moving to the Faculty of Arts, where he eventually became Dean. MacKay was instrumental in limiting the number of Jewish students admitted to the Faculty of Arts. He believed “the Jewish people are of no use to us in this country” and that “as a race of men their traditions and practices do not fit in with a high civilization in a very new country.” In the 2001–2002 academic year, the Law Faculty voted to abolish a student award named in his honour.

Chief Justice Thibaudeau Rinfret Appointed to Supreme Court

Chief Justice Thibaudeau Rinfret (B.C.L. 1900, LL.D. 1944) was appointed to the Supreme Court of Canada in 1924. In 1944, he became the ninth Chief Justice of Canada, a position he held until 1954. In total, he served on the Supreme Court for 30 years, one of the longest tenures in Canadian history. In 1947, Chief Justice Rinfret was also named to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council. He later also served as the first Chairman of the Civil Code Revision Office when the Quebec Government established it in 1955 to review and modernize the Civil Code of Lower Canada.

Chief Justice Thibaudeau Rinfret (B.C.L. 1900, LL.D. 1944) was appointed to the Supreme Court of Canada in 1924. In 1944, he became the ninth Chief Justice of Canada, a position he held until 1954. In total, he served on the Supreme Court for 30 years, one of the longest tenures in Canadian history. In 1947, Chief Justice Rinfret was also named to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council. He later also served as the first Chairman of the Civil Code Revision Office when the Quebec Government established it in 1955 to review and modernize the Civil Code of Lower Canada.

Prior to serving on the Supreme Court of Canada, Rinfret practised law in Quebec and gave lectures at McGill’s Faculty of Law for a decade on municipal law and the law of public utilities. He also briefly sat on the Quebec Superior Court from 1922 to 1924. A francophone, Rinfret was actively involved in the Alliance française and the Association of French-Speaking Jurists.

Marler Family

William De Montmollin Marler, B.C.L. 1872, D.C.L. 1897, LL.D. 1926, left, graduated from McGill with the Elizabeth Torrance Gold medal in 1872 and returned to the Faculty to teach for over 30 years in notarial law and civil law.

George Carlyle Marler, B.C.L. 1922, LL.D. 1965, right, was the son of William de Montmollin Marler who co-authored, edited, and published the Law of Real Property out of his father’s lecture notes. Despite his misgivings, he undertook the publication of the book “in view of the importance of the subject.” The book became a classic and continues to be a leading work on this subject to this day. After publication, George Marler went on to serve in a variety of government positions, including as leader of the Quebec Liberal Party.

Other notable members of the family include Herbert Meredith Marler, B.C.L. 1898, who was the son of William de Montmollin and half-brother of George Marler. Herbert Marler’s career included work as a notary, a seat in the House of Commons, and the posting as Canada’s first ambassador in Asia.

Arnold Wainwright: Major Benefactor

Arnold Wainwright (B.C.L. 1902, D.C.L. 1963) was an Elizabeth Torrance Gold Medalist, professor, successful practitioner, and major benefactor of the Faculty. In 1958, Wainwright purchased and presented the Faculty with a collection of 1,200 volumes on French private law from the French scholar François Olivier-Martin. The collection, one of the most comprehensive in the world, contains many works from the pre-Revolutionary (and pre-codification) period of French law, including early editions of works by Pothier and Domat. The collection is now housed in Nahum Gelber’s Peter Marshall Laing room on the second floor.

Arnold Wainwright (B.C.L. 1902, D.C.L. 1963) was an Elizabeth Torrance Gold Medalist, professor, successful practitioner, and major benefactor of the Faculty. In 1958, Wainwright purchased and presented the Faculty with a collection of 1,200 volumes on French private law from the French scholar François Olivier-Martin. The collection, one of the most comprehensive in the world, contains many works from the pre-Revolutionary (and pre-codification) period of French law, including early editions of works by Pothier and Domat. The collection is now housed in Nahum Gelber’s Peter Marshall Laing room on the second floor.

In 1967, Wainwright bequeathed his estate to the Faculty, leading to the creation of the Wainwright Trust. The Trust has funded scholarships, the Wainwright Fellowships, the Wainwright lecture series, the Wainwright student essay prize, the Wainwright librarian post, and library acquisitions. The Wainwright Fund has also allowed the Faculty’s civil law collection to attain international renown. Since the 1970s, the Fund has provided a certain amount annually to the library for the collection of civil law texts from around the world. Wainwright’s donations have enabled McGill to be a world leader in civil law scholarship.